Bone Cancer

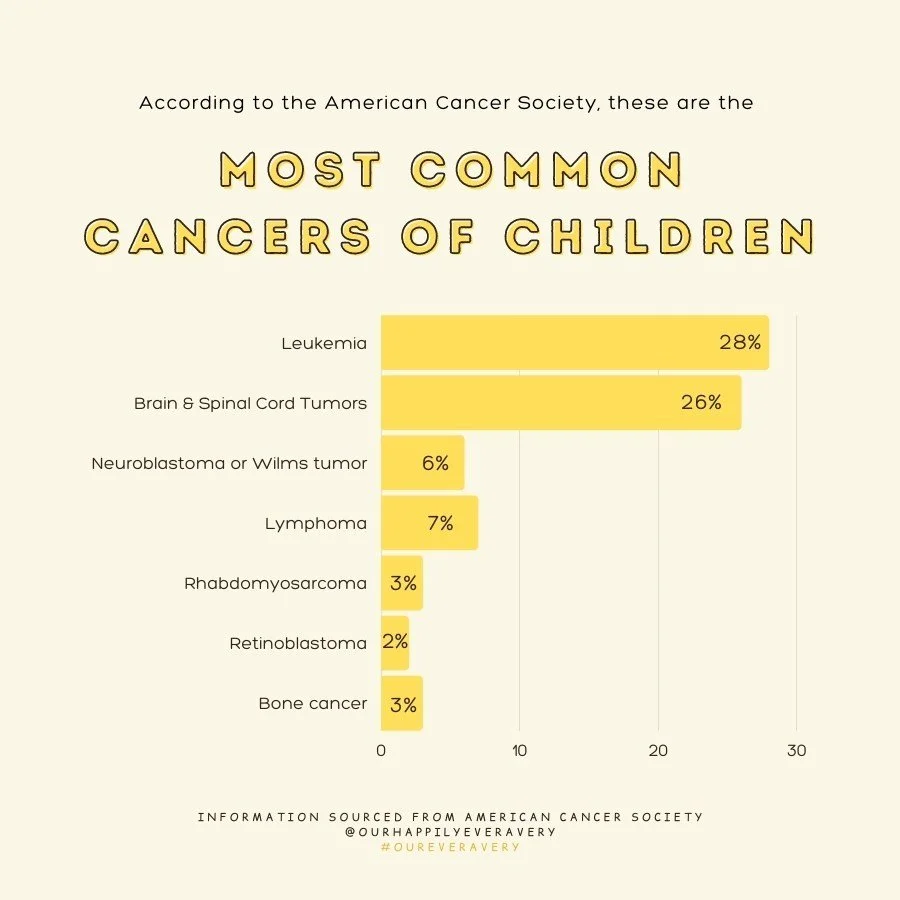

Leukemia, brain tumors, and bone cancers are among the most common childhood cancers. Osteosarcoma is the most frequent bone cancer, usually affecting teens during growth spurts. Ewing Sarcoma is rarer, occurring in both bone and soft tissue, mostly in teens and slightly more often in boys. It accounts for about 1% of childhood cancers, affecting roughly 200–250 children in the U.S. each year.

I was diagnosed with Ewing Sarcoma at just 2 years old, an unusually young age for this type of cancer. The prognosis depends on several factors, including whether the cancer has spread, the patient’s age, and the tumor’s location. In my case, the tumor was confined to my right femur and had not metastasized. Combined with my young age, this gave me a better chance of recovery.

The precise cause of Ewing Sarcoma remains unknown. Researchers have explored possible genetic or hereditary links, but no direct connection has been found. In my family, one of my dad’s cousins died of Ewing Sarcoma at age 20, and my maternal grandmother had non-genetic breast cancer. These separate family cases of cancer made my parents wonder about a possible genetic link, but there is no evidence of it. Current science suggests that Ewing Sarcoma is caused only by a random mutation.

My first symptoms were unexplained limping, fever and pain in my leg. Since I was only two years old, I couldn’t clearly explain what I was feeling, and my parents now encourage others to take unexplained pain in young children seriously.

Diagnosis involved a series of tests: X-rays, MRI, CT and PET scans, blood work, and biopsies. Treatment lasted nearly a year and consisted of surgery and 17 rounds of chemotherapy, with frequent delays due to a weakened immune system and surgical recovery. Radiation was not an option for me because the tumor was located near a growth plate, where radiation could have permanently stopped bone growth. However, radiation is used as part of treatment for Ewing Sarcoma when the tumor’s location and the patient’s condition make it a suitable choice. I was also also enrolled in a chemotherapy clinical trial.

Treatment came with side effects, including hair loss, nausea, and the need for blood transfusions. After treatment, CT chest scans and other follow-up tests were done every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months from years 3 to 5, and annually through year 10. I’ve now passed the 10-year post-treatment mark without any relapses or scares, but still continue to receive echocardiograms every two years to monitor for potential heart damage caused by the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin.