Amputation

After informing my parents that I had Ewing Sarcoma and that amputation would be required as part of the treatment, the orthopedic surgeon presented my parents with three possible options: a straight amputation, tibia turn up, and rotationplasty.

I’ll go through the options in order:

1. Because my tumor was situated above my knee, a straight amputation would have left me with a very short stump, which would have heavily limited my mobility.

2. Tibia turn up remedies the issue of the short stump by fusing part of the tibia to the stump to increase the length of the femur, but it still limits mobility since I would lack any type of knee joint.

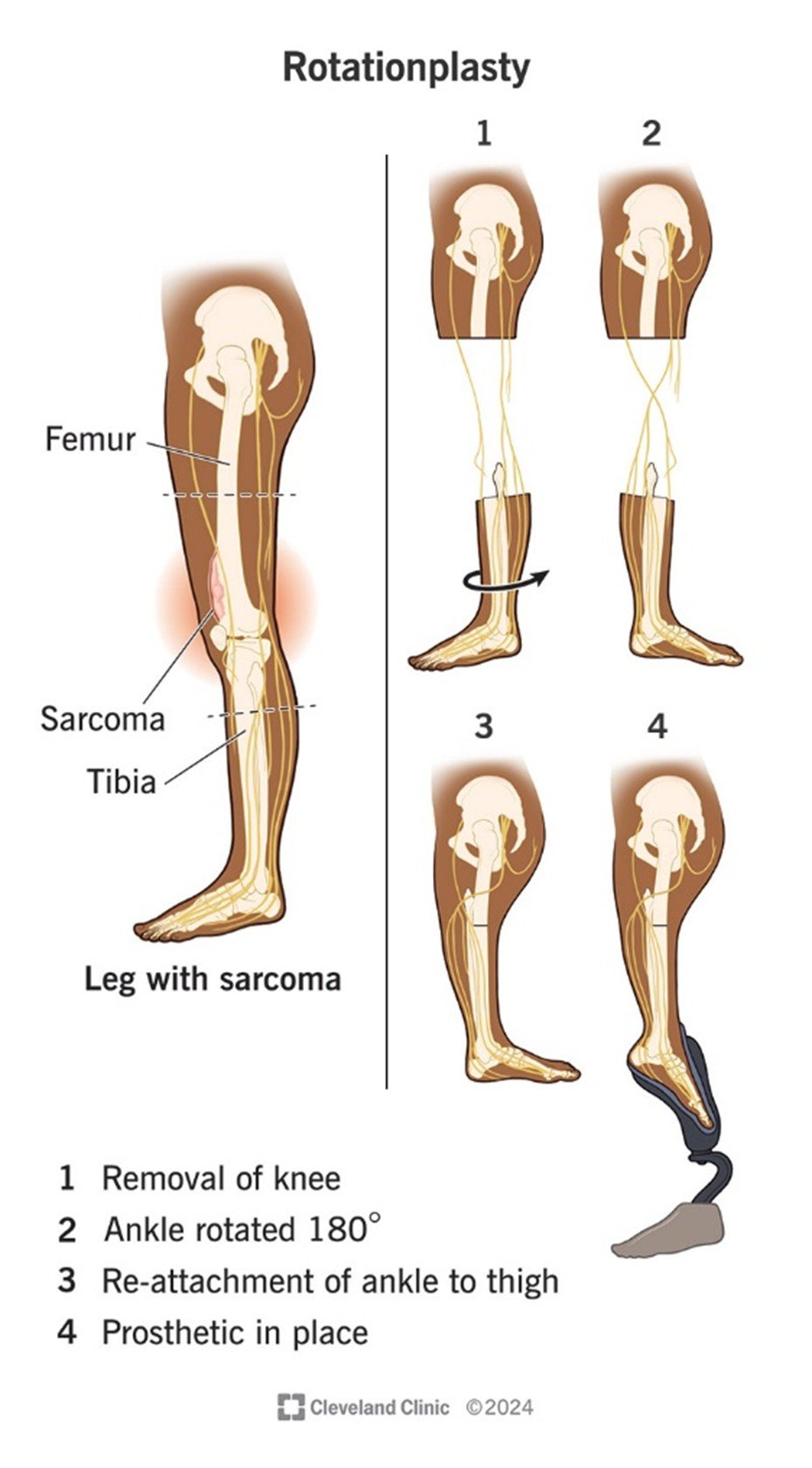

3. Lastly, what my parents chose for me (and what was recommended by the surgeon) was rotationplasty, a rare amputation that offers a lot of advantages. First, it does not lead to phantom pain. Second, it causes what was formerly your ankle joint to act as a replacement knee. While it does not have the full range of motion you would normally have, it still offers a large boost in mobility which is helpful for participating in physical activities. One thing to consider, however, is that it does look very strange (see picture below). The appearance was not really a concern for my parents, and because I have had it since I was very young, its appearance also does not bother me.

A bit more on rotationplasty: as mentioned, its primary benefit is that it rotates the lower leg and fuses it to the stump, allowing for the ankle to function as a replacement knee joint, which enhances mobility especially when combined with a prosthetic. It is most often administered to young children with bone cancer, since their bones are still growing. It can also be used to help congenital defects and, more rarely, traumatic injuries or severe infections in children or adults. Considering the groups it is most commonly given to, it makes sense that rotationplasty is quite rare. Few surgeons have performed it, and those who have generally do it under 10-15 times during their entire career, given that it is quite complex and challenging for surgeons. It is also difficult for the patient, especially since the recovery period can involve many obstacles and unwanted surprises. I was fortunate in that my specific set of circumstance made it an appealing and viable option.

My surgeon was Dr. Rinsky at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (Stanford)—one of the few surgeons in the country who perform rotationplasty surgery. By the time I became his patient, Dr. Rinsky had completed about 10 rotationplasty surgeries, which is considered quite a high number given how rare and complex the procedure is.

Before the surgery, I went through six rounds of chemotherapy to shrink the tumor. To help me understand what was coming, my parents showed me videos of rotationplasty and walked me through what the procedure would involve.

The surgery took place on October 10, 2011, and lasted about 10 hours. Thankfully, it was a success. Because I was so young at the time, I was able to adjust to the change without too much distress. Recovery, however, was slow. I ended up needing a follow-up surgery to repair the wound, which delayed my return to chemotherapy. I had been scheduled to resume treatment two weeks after the operation, but because of the complication, it was pushed to mid-November.

In March 2012, while I still had three more rounds of chemo to go, I began the process of getting fitted for a prosthetic leg. I received my first prosthetic in April, and completed my final round of treatment in May. A few months later, in September 2012, I had another surgery—this time to fuse the bones. The intense chemotherapy I had gone through earlier had prevented them from fusing properly on their own. In this operation, the surgeons shaped the ends of the bones so they would fit together more securely—almost like joinery in woodworking—and used a paste made from bone matter to help stimulate healing and fusion.

Because of my age, I was able to adapt fairly quickly and needed less physical therapy than many older patients might have. By the end of 2012, I had gradually returned to my normal activities. There were definitely challenges along the way, especially with getting a prosthetic that worked well for me. It wasn’t until we found Shriner’s Hospital for Children that things started to really improve.

Since then, things have been going well. I have been able to do pretty much everything I have wanted to do physically. I did not experience any complications or side effects from surgery.